|

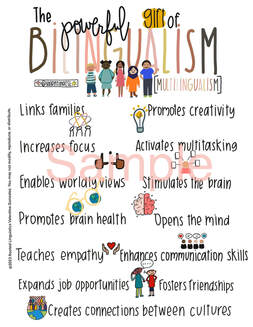

This is a monolingual brain. This is a brain on multiple languages. In a globalized society, it is a disadvantage to understand and speak a single language. Nations work together to solve problems as well as communicate and work alongside one another. Therefore, one who is able to speak and understand multiple languages has apparent advantages in communication over one who can not. Let’s examine the brain, languages, and how this plays out in our classrooms. Monolingual people can become bilingual or even multilingual! The brain is a magnificent organ. And scientists continue to study it and learn about it. Though there is research on multilingual brains, the research is still very new. It wasn’t long ago that experts believed bilingualism slowed learning. Only a few years ago was it believed that different languages were housed in separation in the brain. Recent research has proven that wrong, and now we know that languages are not separated in different parts of the brain. As people acquire languages, the brain actually changes. Yet being bilingual or multilingual is not just about knowing more words. In the Power of Language (2023), Viorica Marian says, “It rewires your brain and transforms it, creating a denser tapestry of connectivity.” The linguistic advantages of knowing more than one language seem obvious. But what about the cognitive? Studies have shown that people who are bilingual or multilingual are able to complete cognitive tasks that test attention span, memory, and moving from one task to another faster than their monolingual peers. These abilities seem like obvious advantages. Having a greater attention span can be helpful to us in school and beyond. Having the capacity to remember information is also quite useful. And ultimately the aptitude to go from one idea to another also seems to add benefit to one's life. Some studies indicate that being bilingual may slow cognitive decline, possibly delaying the onset of diseases like Alzheimer's and dementia. Living healthier lives means that bilingual people have a greater chance of living longer lives too. But if you were a fly on the wall of a typical middle school classroom, you might not hear many languages other than English being spoken. Kids are often ashamed of their home languages, and they sometimes don’t feel the power of bilingualism at a young age. Many parents complain that their children don’t want to speak their home language and that as their kids get older, they only want to speak English. Yet, once these same kids enter adulthood, many realize the power of bilingualism and begin to regret the languages they lost. In the Classroom How do students experience language in our schools and classrooms? What messages about language do students receive both explicitly and implicitly? As educators, one of our roles is to create strategic experiences for students to use language, to practice pulling from their full repertoire. We can carefully design lessons that provide pathways for students to engage with peers, speak, listen, and think using the linguistic assets they have.

What we can do:

It’s simply not enough to tell students that being bilingual is powerful. We have to quantify it. What we do in the classroom has to match what we say. Only then will students begin to internalize the belief.

Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed