|

I have fond memories of cuddling up next to my tata (Serbian for daddy) before bedtime and listening anxiously as he told stories he remembered or even ones he made up. As an immigrant family from the former Yugoslavia, we brought little with us when we came to America. Books were heavy and did not make the journey. Storytelling, however, was a cherished time in our home. My favorite story was Hansel and Gretel. **a version of this blog post was first published on BookBuzz. My childhood home was not filled with bookshelves lined with books. I didn’t have a stack of books to read in my bedroom. Nor do I remember sitting on mama’s or tata’s lap as we turned the pages of a book. But I can still hear the sound of my grandmother’s voice singing Serbian songs and reading the poetry that she wrote in her notebook, her handwriting a mystery to my eyes. My first formal introduction to English was as a kindergartener. I loved school. I soaked it up like a sponge and admired my teacher as if she were a queen. My favorite part of the day was when she read aloud to us. I loved watching as she melodically formed the words and gracefully turned pages. One magical day as she read, I realized that the story she was reading to us in English was the bedtime story my dad told me at home in Serbian. It was Hansel and Gretel! The two people I adored more than anyone else knew the story I loved most and in two languages! I was in disbelief. Until that day, it always seemed to me that my home life and language were completely separate from my school life and language. But that day they met! And it was magical. I have mixed emotions about this memory. It makes me sad because it was one of the only times that I felt as if a little part of my home life and culture came to school with me. For years after that experience, I struggled to connect with books. I rarely found myself in literature or read about my lived experiences. As an educator, this reminds me that children should not have to shed their identity, their language, literacy, and who they are at home when they come to school. On the other hand, the memory makes me happy because it reminds me that we can create great places in our classrooms that open students’ hearts and minds and builds joy for reading. We can help children feel seen, heard, and valued. We can embrace cultures and identities. We have the power to make an enormous impact on readers in our classrooms every day. By the year 2025 it’s estimated that 1 in 4 students in the United States will be classified as English learners (ELs). That number is remarkable! ELs, or multilingual learners (a more asset- based term) are the fastest-growing population of students in our nation. And they bring many valuable attributes, lived experiences, and qualities that can be leveraged in our classrooms. One of the greatest strengths we each have is our identities as unique humans. So how can we support multilingual children in our classrooms as readers? What would this look like on Monday morning? As a teacher, I worked on a campus that served multilinguals that spoke over 20 different languages. Of course, I could not speak all of them. But there were things I could do even though I did not serve in a bilingual program. The following are three practical suggestions for supporting multilingual readers in any classroom. 1. Partner with parents, families, and caregivers. Parents are often a child’s first teachers and know their children best. They can provide us with valuable information about students’ lives, passions, strengths, etc. We can use this information to connect them with books they will love. Partnering will also help us to create a team for literacy and reading growth. On the other hand, we also have a lot to offer to parents, families, and caregivers. Through a partnership, we can:

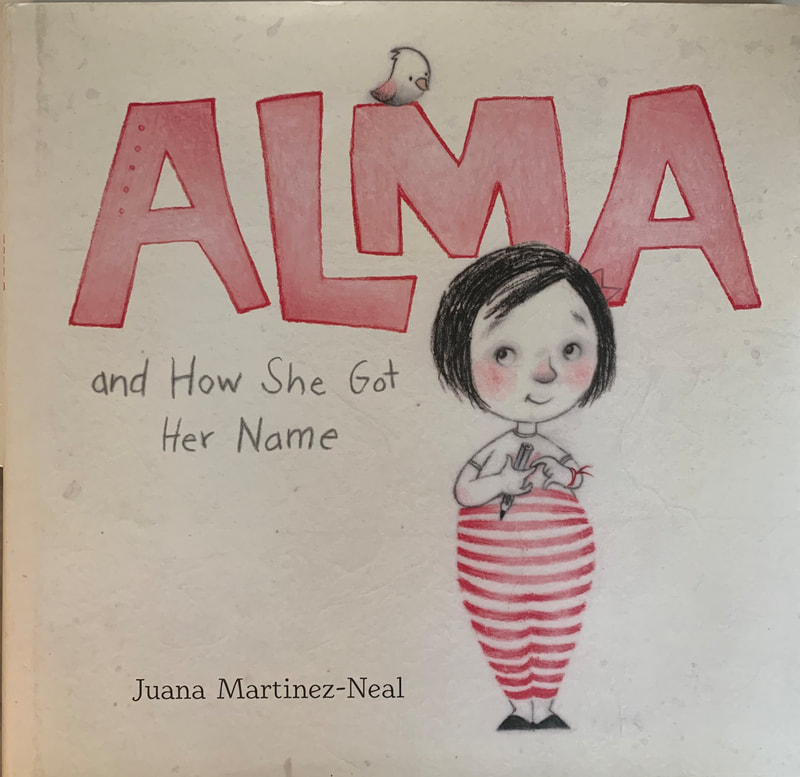

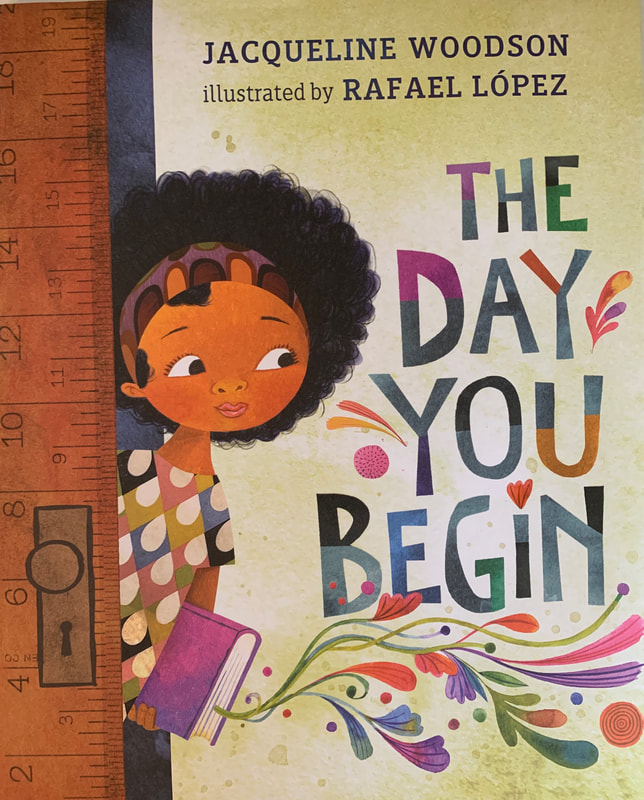

2. Ensure that the books offered on shelves represent the students in the classroom. Rudine Sims Bishop (1990) calls this mirrors. Recent studies on published children’s literature have shown that a great proportion of books offer main characters that are White and those that are minorities are often misrepresented or stereotypes. Diversity in children’s literature still has a long way to come. When I first learned about these studies, I didn’t think my own library shelves were out of proportion, but I was shocked when I took an audit. That audit prompted me to take action. Each time my district offered funds that I could use for books, I applied that money towards books that my students could connect with. It was important to me that the books were not solely for the ESL classroom. The goal was for the books to be in every classroom, accessible as read-alouds and for students to enjoy on their own as independent reading. This is just a sampling of the books we purchased: 3. Team up with the campus library media specialist. Work together to build more inclusive multilingual book offerings to the campus library. The librarian that I worked with used Follett Titlewave. We pulled up the top languages spoken on our campus and we began ordering the most popular books in multiple languages. Students that can read in multiple languages have unique linguistic capital that not everyone has. We can embrace and support biliterate children and their linguistic identities by providing books in the languages they read. They are future global leaders!

When literacy (in all languages) is seen from an asset perspective, nurtured, and valued all stakeholders benefit. I learned along the way to allow myself the autonomy to be flexible in teaching and learning and to let students lead. Centering instructional practices and all that I do around them changed how we learned, how much we learned, and how much joy we all had in learning. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed